Lyme disease, also known as Lyme borreliosis, is a vector-borne disease that is found in canines, humans, and occasionally in felines. Lyme disease is caused by a bacterium, Borrelia burgdorferi. It can’t survive in the environment without a host.

Lyme disease, also known as Lyme borreliosis, is a vector-borne disease that is found in canines, humans, and occasionally in felines. Lyme disease is caused by a bacterium, Borrelia burgdorferi. It can’t survive in the environment without a host.

Transmission

Transmission

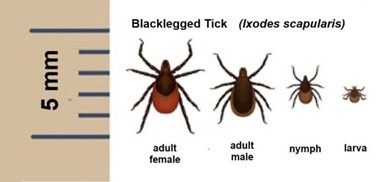

The insect vector that carries Lyme are ticks. In North America, focusing in Northeast, the Deer Tick aka Black-legged tick, Ixodes Scapularis, carries this infectious disease. The tick has to bite its host, whether that is your dog, cat, or yourself. In order for the Lyme disease to be transmitted into the host it needs to be attached for 36-48 hours.

Transmission in felines is rare because cats are resistant to the bacteria, Borrelia burgdorferi, that causes Lyme disease. They also groom themselves often, leaving the tick very little to no time to attach and infect your cat.

Symptoms

In canines, some will experience random points of arthritis pain or discomfort after the disease has been manifesting for weeks to months. In acute cases they will present with a fever as well as joint pain. In more severe cases they can develop kidney disease, heart, and neurologic abnormalities.

In felines, symptoms are fever, lethargy, decreased appetite, and sore or stiff muscles and joints much like dogs.

Prevention / Recontamination

There are many preventives, such as collars, topicals, and chewable tablets. Most preventatives are for dogs, but there are options for cats. The products recommended by veterinarians for dogs include: Bravecto, Simparica, Simparica Trio, Frontline Gold, NexGard, Seresto Collars, and Credelio. For cats, again veterinarian recommended include: Revolution plus, Bravecto Plus, Seresto collars, Frontline Plus, and Credelio. Although your cat is less likely to contract Lyme disease, the tick could travel from your cat to you and get you infected.

Recontamination can occur. Meaning, if your dog gets Lyme disease and is treated but isn’t on a preventative to avoid more tick bites, they could get re-infected with the disease and need treatment all over again. It is crucial to keep your dogs and cats on year-round protection to reduce the risk of Lyme disease and recontamination.

Testing

Originally blood laboratory tests including: PCR, ELISA, Western Blot, joint fluid analysis were performed. Now there are two tests called Lyme C6 and Lyme Quantitative C6. The Lyme C6 test mostly checks for antibodies against the protein called C6; results are positive or negative. The Lyme Quantitative C6 test determines the level of antibodies; results give you a number with the unit IU/mL. If the C6 is positive then your veterinarian will send for the QC6 and if the result is greater than 30 IU/mL and your dog is having symptoms treatment would be necessary. If the QC6 results were less than 30 IU/mL and your dog isn’t symptomatic than treatment isn’t needed. Keep in mind if your dog has a QC6 result over 30 IU/mL but not symptomatic it would still be recommended to get treatment because over time symptoms could get worse.

Other tests might include routine blood work and urine sample to check kidney function. The reason for these tests is to check the protein levels to check for early underlying kidney disease due to the Lyme disease.

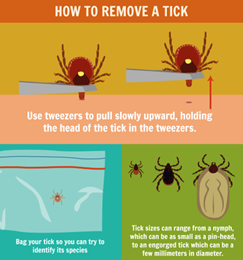

How to remove a tick

How to remove a tick

Use tweezers to grab the tick as close the surface of the skin as you can. Then pull upward with steady, even pressure. Don’t twist the tick because the mouth could break off. If you pull on the tick and a portion of the head is still in the skin, don’t worry – the portion left over will scab over and fall out on its own. Clean the bitten area with rubbing alcohol or soap and water. Drown the tick it in alcohol in a sealed container. Never kill the tick with your fingers.

Treatment

Lyme disease is usually treated with four weeks of antibiotics. The antibiotic commonly used is Doxycycline. Most dogs have obvious improvement 48 hours after starting treatment. It is recommended to retest the QC6 six months after treatment is completed. If the QC6 results has dropped 50% or more, extended treatment is likely not needed. But, if the QC6 results haven’t dropped by at least 50%, retreatment of Doxycycline would be warranted.

Written by Jackie Brochu, Veterinary Technician

Citations

Brooks, Wendy. “Lyme Disease in Dogs.” VIN, 6 Dec. 2003, https://veterinarypartner.vin.com/default.aspx?pid=19239&id=4952009.

“Lyme Disease: A Potential, but Unlikely, Problem for Cats.” Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, 21 May 2018, https://www.vet.cornell.edu/departments-centers-and-institutes/cornell-feline-health-center/health-information/feline-health-topics/lyme-disease-potential-unlikely-problem-cats#:~:text=Lyme%20disease%20is%20probably%20not,outside%20of%20a%20laboratory%20setting.

Llera, Ryan, et al. “Testing for Lyme Disease in Dogs: VCA Animal Hospital.” VCA, https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/testing-for-lyme-disease-in-dogs#:~:text=The%20traditional%20blood%20tests%20(PCR,very%20specific%20protein%20called%20C6.

Lundgren, Becky. “Ticks Are Arthropod Parasites for Mammals.” VIN, 29 May 2006, https://veterinarypartner.vin.com/default.aspx?pid=19239&id=4952474#:~:text=Pull%20upward%20with%20steady%2C%20even,and%20let%20the%20skin%20heal.

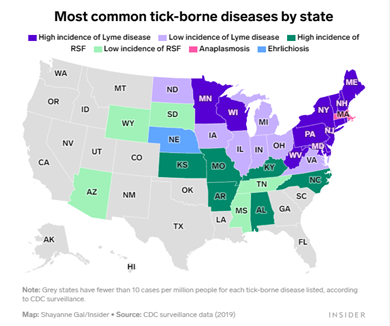

Michelson, Andrea. “Most common tick-borne diseases by state”. Map shows which tick-borne disease is most common in your state, 10 May. 2022. https://www.insider.com/map-states-with-lyme-disease-other-tick-borne-illnesses-2022-5

Whitley, Amy. “Types of Ticks and Where They Live”. Tick Dangers and Precautions While RVing. 2008-2022. https://www.everything-about-rving.com/tick.html

Whitley, Amy. “How to Remove a Tick”. Tick Dangers and Precautions While RVing. 2008-2022. https://www.everything-about-rving.com/tick.html

“Blacklegged Tick (Ixodes scapularis)”. What percentage of deer ticks in Connecticut carry Lyme disease. 3 June 2020. https://hartfordhealthcare.org/about-us/news-press/news-detail?articleId=1738&publicid=462